Occupation of Haiti

| United States occupation of Haiti | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Banana Wars | |||||||

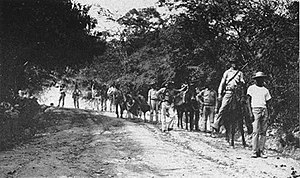

United States Marines and a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle in 1915 during the Battle of Fort Dipitie |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First Caco War: 1,500 |

First Caco War: 2,700 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

First Caco War: 28 killed |

First Caco War: 70 killed |

||||||

American victory

First Caco War:

2,029

First Caco War:

5,000

First Caco War:

3 KIA, 18 WIA

First Caco War:

200 killed

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 US Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on the authority of US President Woodrow Wilson. The first invasion forces had already disembarked from USS Montana on January 27, 1914. The July intervention took place following the murder of dictator President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam by insurgents angered by his political executions of elite opposition.

The occupation ended on August 1, 1934, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt reaffirmed an August 1933 disengagement agreement. The last contingent of US Marines departed on August 15, 1934, after a formal transfer of authority to the Garde d'Haïti.

Between 1911 and 1915, Haiti was politically unstable: a series of political assassinations and forced exiles resulted in six presidents holding office during this period. Various revolutionary armies carried out the coups. Each was formed by cacos, or peasant brigands from the mountains of the north, or who invaded along the porous Dominican border. They were enlisted by rival political factions under the promises of money, which would be paid after a successful revolution, and the opportunity to plunder.

The United States was particularly apprehensive about the roles (real and imagined) played by Imperial Germany in the Western hemisphere. Controlling Tortuga, it had intervened in Haiti (see Luders Affair) and other Caribbean nations at several times during the previous few decades to exert its influence as a rival power. Germany was increasingly hostile to United States domination of the region under its claimed Monroe Doctrine. In the lead-up to the World War I, the strategic importance of the island of Hispaniola, with its manpower, material wealth, and port facilities, was understood by almost all navies operating in the Caribbean, including Germany and the still-neutral United States. Germany had invested in military and intelligence gathering across Hispaniola as part of a wider network of German interest in Latin America and the Caribbean during the 1890s through the 1910s.

...

Wikipedia