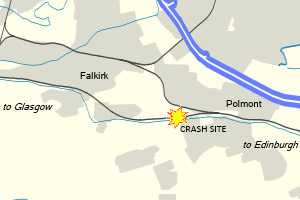

Polmont rail crash

Approximate location of the Polmont rail accident

|

|

| Date | 30 July 1984 |

|---|---|

| Time | 17:55 (BST) |

| Location | west of Polmont 21.5 mi (34.6 km) west-northwest from Edinburgh |

| Coordinates | 55°59′04″N 3°44′42″W / 55.9845°N 3.7450°WCoordinates: 55°59′04″N 3°44′42″W / 55.9845°N 3.7450°W |

| Country | Scotland |

| Rail line | Glasgow to Edinburgh via Falkirk Line |

| Operator | British Railways Scottish Region |

| Type of incident | Derailment |

| Cause | Obstruction on line |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | 150+ |

| Deaths | 13 |

| Injuries | 61 (17 serious) |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The Polmont rail accident, also known as the Polmont rail disaster, occurred on 30 July 1984 to the west of Polmont, near Falkirk in Scotland, when a westbound push-pull express train travelling from Edinburgh to Glasgow struck a cow which had gained access to the track through a damaged fence from a field near Polmont railway station. The collision caused all six carriages and the locomotive of the train to derail, killing 13 people and injuring 61 others. The accident led to a debate about the safety of push-pull trains on British Rail.

The accident happened on one of the busiest commuter lines in Scotland. At the time of the accident, British Rail passenger trains between Glasgow Queen Street and Edinburgh Waverley were operated by the push-pull technique with a single British Rail Class 47 locomotive located at one end of the train at all times (usually the locomotive pulled the carriages from Glasgow to Edinburgh and pushed on the return journey). At the other end of the train was a Driving Brake Standard Open (DBSO). DBSO carriages were introduced on the line in 1980 and consisted of a passenger carriage with a control cab at the front for the driver; a DBSO would be situated at the front of the train allowing the driver to control the locomotive with a set of remote controls from which control signals were sent through the lighting circuits of the train to the locomotive pushing from behind. This system meant that the train could continuously run between the two cities without having to allow time to switch the locomotive to the front of the train between departures. However, it left the front of the train vulnerable when being pushed from behind because the front end was lighter than the rear and had the risk of being pushed over an obstruction, leading to derailment.

...

Wikipedia