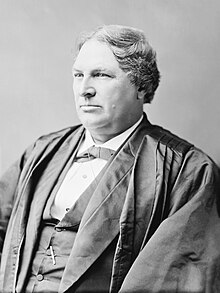

Samuel Freeman Miller

| Samuel Miller | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office July 16, 1862 – October 13, 1890 |

|

| Appointed by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Peter Daniel |

| Succeeded by | Henry Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

April 5, 1816 Richmond, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 13, 1890 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party |

Whig (Before 1854) Republican (1854–1890) |

| Education | Transylvania University (MD) |

Samuel Freeman Miller (April 5, 1816 – October 13, 1890) was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court who served from 1862 to 1890. He was a physician and lawyer.

Born in Richmond, Kentucky, Miller was the son of yeoman farmers. He earned a medical degree in 1838 from Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. While practicing medicine for a decade, he studied the law on his own and was admitted to the bar in 1847. Favoring the abolition of slavery, which was prevalent in Kentucky, he supported the Whigs in Kentucky.

Miller moved to Keokuk, in Iowa, a state more amenable to his views on slavery. Active in Hawkeye politics, he supported Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Lincoln nominated Miller to the Supreme Court on July 16, 1862, after the beginning of the American Civil War. His reputation was so high that Miller was confirmed half an hour after the Senate received notice of his nomination.

His opinions strongly favored Lincoln's positions, and he upheld his wartime suspension of habeas corpus and trials by military commission. After the war, his narrow reading of the Fourteenth Amendment—he wrote the opinion in the Slaughterhouse Cases—limited the effectiveness of the amendment. Miller wrote the majority opinion in Bradwell v. Illinois, which held that the right to practice law was not constitutionally protected under the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

He later joined the majority opinions in United States v. Cruikshank and the Civil Rights Cases, holding that the amendment did not give the U.S. government the power to stop private—as opposed to state-sponsored—discrimination against blacks. In Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U.S. 651 (1884), however, Miller held that the federal government had broad authority to act to protect black voters from violence by the Ku Klux Klan and other private groups. Miller also supported the use of broad federal power under the Commerce Clause to trump state regulations, as in Wabash v. Illinois.

...

Wikipedia